The Opium Act of 1908 makes it an offense to import, manufacture, possess or sell opium for non-medical reasons in Canada. People who are found in violation of the statute may be punished by incarceration of up to three years and/or a fine of up to $1,000.

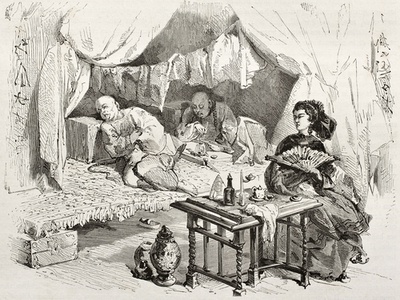

This legislation was largely motivated by a desire to regulate Chinese residents of Canada. After anti-Asian sentiment led to labour riots against Chinese and Japanese residents of Vancouver in 1907, William Lyon Mackenzie King was appointed by Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier to deal with the aftermath of the situation. While King sorted out claims for the damage that had been done to Asian businesses during the riots, he noted that one of the Chinese businesses claiming damages was an opium factory and was shocked by the scope of the opium trade.

Laurier then sent King on a world tour to figure out how to deal with issues surrounding immigration from Asia. The solution? Make up a benevolent pretext - Asians cannot survive the cold Canadian winters - it doesn't have to be true. When King returned to Ottawa, he proposed an Opium Law saying, "We will get some good out of this riot yet." Rather than addressing the labour disputes between white and Chinese workers, King shifted the problem to opium use by Asian foreigners. The law was easily passed within a few weeks and has defined Canadian drug policy for over a century.

Source: Report of the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs. Vol 2: Part III. (2002).

| Drugs: |

Opium (morphine, heroin, opioids) |

| Regions: |

Canada |

| Topics: |

Cultivation, production and trade, Cultural factors (social, religious, ritual), Prohibition, Taxation and regulation |

External Links

Cannabis: Our Position for a Canadian Public Policy

Report of the Senate Special Committee on Illegal Drugs (2002) Chapter 12

The Riot that Changed Canada

An article by Crawford Kilian in the 3 July 2015 issue of The Tyee.

Related Timeline Items

Opium dens appear in Vancouver and Victoria (1890 CE)

Chinese immigrants first established Chinatowns in Victoria and Vancouver in British Columbia, and here too, opium dens were common in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. When the city of San Francisco began taxing imported opium for smoking, the trade was diverted to Victoria, and, from there, much of the opium was smuggled south into the United States. However, a fair amount of opium was consumed in the opium dens to be found in the Chinatowns of Victoria and Vancouver. The latter city's "Shanghai Alley" was known for its rustic opium dens. As in the United States, non-Chinese often frequented the Chinese-run opium dens in Canadian Chinatowns

The Smoking Opium Exclusion Act (USA) prohibits opium for smoking (1909 CE)

In 1909, the United States makes the importation of opium illegal. However, only the importation of opium prepared for smoking is banned, while the medicinal opium that white Americans commonly kept in their household medicine cabinets can still be imported.

Anti-Chinese sentiments shapes the context around the passing of this exclusion act. The law was specifically aimed at a particular way of using the drug that targeted the Chinese, not at the drug itself. Public opium dens had been outlawed in 1875 in San Francisco, as opium smoking had come be seen as unfavourable and foreign by temperance advocates and moral reformers.

Cannabis is outlawed in Canada (1923 CE)

In 1923, Cannabis was added to the schedule of the Opium and Narcotic Control Act, effectively making it illegal to use in Canada. Both the House of Commons and the Senate agreed to the addition without any discussion at all. This raises the question, Why was cannabis criminalized without debate?

Seems there was a draft of the bill that did not include cannabis, but, on one of the carbon copies, an unknown scribe scribbled "Cannabis Indica (Indian Hemp) or hasheesh" in the margin. No one knows who added that phrase, or ordered it added.

Two social forces at the time may have contributed to the ease with which cannabis prohibition was passed. Police forces were actively campaigning for increased powers and restrictions on civil liberties. Simultaneously, there was widespread panic in Canada inspired by an anti-drug, anti-Chinese campaign led by editorials and articles in the Vancouver Daily Sun and Maclean's.

When Deputy Minister of Labor, Mackenzie King, visited British Columbia to investigate the labour riots of 1907, he was shocked by the scope of the opium trade.