Related Timeline Items

English Parliament promotes gin production (1713 CE)

The English Parliament in 1713 declared: “Any person may distil . . . spirits from British Malt.” All sorts of people tried their hands, using facilities ranging from purpose-built copper stills to converted washtubs. Among them they produced a torrent of gin, which was sold from shops, houses, the crypts of churches and inside prisons, from kiosks, boats, wheelbarrows, baskets and bottles, and from stalls at public executions. In the London parish of St. Giles-in-the-Fields, whose fields were now slums, one house in every five retailed gin. Most of it was offered by the dram, or quarter pint. Gin was a cheap, and above all a quick, way of getting drunk. Why work your way through porter at three pence a pot when the same money would buy a pint of gin?

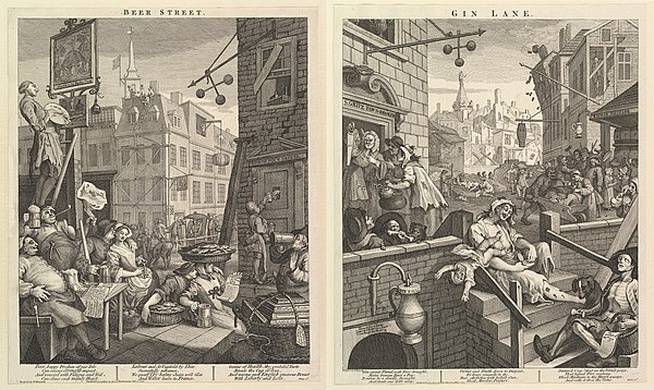

The London "gin craze" (1720 - 1757 CE)

Efforts by the English king and Parliament to encourage production of gin to increase the price of grain and to provide tax revenue drove the price of gin down and consumption way up particularly among the poor.

Tobias Smollet, a physician, wrote that gin "was sold so cheap that the lowest class of the people could afford to indulge themselves in one continued state of intoxication, to the destruction of all morals, industry and order. Such a shameful degree of profligacy prevailed that the retailers of this poisonous compound set up painted boards in public, inviting people to be drunk for the small expense of one penny; assuring them they might be dead drunk for two-pence, and have straw for nothing."

Britain was an unstable place at the time—religious dissent, rebellion, corrupt politicians and displaced people flocking to the cities all contributed to the instability. The situation was made worse by the squalid living conditions in the slums. People were packed, ten per room, in dirty tenement houses. The only recreation or relief they could afford was gin. As one woman in 1725 said, “We market women are up early and late, and work hard for what we have” and if it were not for gin, “we should never be able to … keep body and soul together.” Between 1730 and 1749, seventy-five percent of all children born in London died before the age of five. Working conditions were brutal and dangerous. Crime increased and highwaymen became folk heroes of the poor.

As gin consumption went up among the poor, the upper classes of British society began to blame gin for all social ills. Wild stories were published in the press about mothers murdering their own children to sell their clothes to buy gin. Gin was reported to result in babies being born shriveled and looking old. And it was feared that gin made people unable to work or defend their country as soldiers, to produce or to consume the right things to keep the economy functioning.

Eventually the government was forced to try control the gin craze through a series of Gin Acts.

British Parliament takes action against gin (1729 - 1743 CE)

In 1729 the British Parliament decided it must curb the gin craze. The first critics of the gin craze had been the brewers who in 1726 wrote a satirical pamphlet about a scuffle between Swell-gut (a brewer) and Scorch-gut (a gin distiller) whose "damn’d devil’s piss burnt out the entrails of three-fourth’s of the King’s subjects.” The distillers had replied "“the Landed Gentleman must be sensible the distillers work for him, since the distilling trade in and about London only, consumes about 200,000 quarters of corn, and that corn necessarily employs 100,000 acres of land.” Economic interests were obviously at stake.

The 1729 Gin Act restricted retail sales of gin to licensed premises and set a high price for licenses. These measures were by and large ignored.

In 1733, Parliament passed a new Gin Act that took a liberal approach. There was a grain surplus once again. Taxes on distillation were reduced, and export subsidies were introduced along with various petty restrictions on unlicensed gin sellers. Consumption again went up, and horror stories were widely reported in the press.

In 1736, a new act introduced large fines for home distilling and raised the license fee for retailing spirits. It relied on informers for enforcement. The new act had as little effect as its predecessors, and the London crowds chanted, "No gin, no king," referring to the unpopular George II. Despite increasingly harsh measures by the government to control gin consumption, nothing much changed for the next seven years.