Related Timeline Items

William of Orange secures the English throne with gin (1688 - 1690 CE)

William of Orange was placed on the throne of England in 1688 after the Glorious Revolution that ousted James II. England was a mess. Affluence and extreme poverty existed side by side in London. “A Tallow Chandler shall front my Lord’s nice Venetian Window; and two or three naked Curriers [leather dressers] in their pits shall face a fine lady in her back closet, and disturb her spiritual thoughts.” What's more, England had a glut of grain so the landowners, who had put William on the throne, could not sell their crops.

William who understood how Genever (gin) had created a demand for grain in his native Holland and was anxious to please the landowners, introduced a law that allowed anyone in England to distill alcohol using English grain. It was a great success—stills sprang up all over the country converting low quality grain into gin and taxes rolled into the treasury.

The London "gin craze" (1720 - 1757 CE)

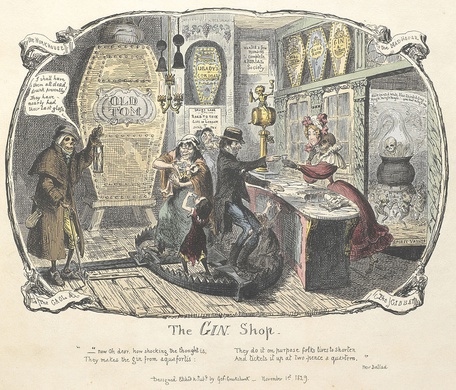

Efforts by the English king and Parliament to encourage production of gin to increase the price of grain and to provide tax revenue drove the price of gin down and consumption way up particularly among the poor.

Tobias Smollet, a physician, wrote that gin "was sold so cheap that the lowest class of the people could afford to indulge themselves in one continued state of intoxication, to the destruction of all morals, industry and order. Such a shameful degree of profligacy prevailed that the retailers of this poisonous compound set up painted boards in public, inviting people to be drunk for the small expense of one penny; assuring them they might be dead drunk for two-pence, and have straw for nothing."

Britain was an unstable place at the time—religious dissent, rebellion, corrupt politicians and displaced people flocking to the cities all contributed to the instability. The situation was made worse by the squalid living conditions in the slums. People were packed, ten per room, in dirty tenement houses. The only recreation or relief they could afford was gin. As one woman in 1725 said, “We market women are up early and late, and work hard for what we have” and if it were not for gin, “we should never be able to … keep body and soul together.” Between 1730 and 1749, seventy-five percent of all children born in London died before the age of five. Working conditions were brutal and dangerous. Crime increased and highwaymen became folk heroes of the poor.

As gin consumption went up among the poor, the upper classes of British society began to blame gin for all social ills. Wild stories were published in the press about mothers murdering their own children to sell their clothes to buy gin. Gin was reported to result in babies being born shriveled and looking old. And it was feared that gin made people unable to work or defend their country as soldiers, to produce or to consume the right things to keep the economy functioning.

Eventually the government was forced to try control the gin craze through a series of Gin Acts.

British Parliament takes action against gin (1729 - 1743 CE)

In 1729 the British Parliament decided it must curb the gin craze. The first critics of the gin craze had been the brewers who in 1726 wrote a satirical pamphlet about a scuffle between Swell-gut (a brewer) and Scorch-gut (a gin distiller) whose "damn’d devil’s piss burnt out the entrails of three-fourth’s of the King’s subjects.” The distillers had replied "“the Landed Gentleman must be sensible the distillers work for him, since the distilling trade in and about London only, consumes about 200,000 quarters of corn, and that corn necessarily employs 100,000 acres of land.” Economic interests were obviously at stake.

The 1729 Gin Act restricted retail sales of gin to licensed premises and set a high price for licenses. These measures were by and large ignored.

In 1733, Parliament passed a new Gin Act that took a liberal approach. There was a grain surplus once again. Taxes on distillation were reduced, and export subsidies were introduced along with various petty restrictions on unlicensed gin sellers. Consumption again went up, and horror stories were widely reported in the press.

In 1736, a new act introduced large fines for home distilling and raised the license fee for retailing spirits. It relied on informers for enforcement. The new act had as little effect as its predecessors, and the London crowds chanted, "No gin, no king," referring to the unpopular George II. Despite increasingly harsh measures by the government to control gin consumption, nothing much changed for the next seven years.

The hypocrisy in gin control exposed (1743 CE)

By 1743, the British Parliament was committed to enacting a gin law that would be obeyed. Lord Lonsdale pointed out during debate on the matter that the discriminatory nature of previous laws had made the people “more fond of dram drinking than ever; because they then began to look upon it as an insult upon the rich.” No restrictions had ever been imposed on the wine and brandies of the upper classes who also drank a huge amount (including the Prime Minister).

The government needed more money to fund a new war in Europe. Some were suggesting a "patriotic" excise tax on gin. Lord Hervey, however, argued, "We have mortgaged almost every fund that can decently be thought of; and now, in order to raise a new fund, we are to establish the worst sort of drunkenness by a law, and to mortgage it for defraying an expense which, in my opinion, is both unnecessary and ridiculous. This is really like a tradesman’s mortgaging the prostitution of his wife or daughter, for the sake of raising money to supply his luxury or extravagance. . . . The Bill, my lords, is . . . an experiment . . . of a very daring kind, which none would hazard but empirical politicians. It is an experiment to discover how far the vices of the population may be made useful to the government, what taxes may be raised upon a poison, and how much the court may be enriched by the destruction of the subjects."

Parliament settled on a compromise—a strict licensing system, with affordable licenses and an excise paid by distillers. Its aims were to restrict demand with high prices, yet not so high as to encourage black market distillation. It also set a precedent by introducing the concept that the taxation of alcoholic beverages should be on a sliding scale and rise in direct proportion to their strength. The 1743 Gin Act was a qualified success, until 70,000 demobilized soldiers returned from the wars in Europe with no jobs to go to and no arrangements for their support. Disorder returned.

A new Gin Act, a new London (1751 CE)

In 1751 a new and final Gin Act was introduced by the British government, which was both pragmatic and successful. It increased taxes, controlled licensing, and banned the sale of spirits on credit. In 1751, about 7 million gallons of gin were taxed, the following year less than 4.5 million. The fall reflected declining demand, rather a shift from the official to the black market. Best of all, the common people responded positively to the new legislation.

London in 1750 was no longer the rowdy place it had been at the turn of the century. The first half of the eighteenth century had been one of crazes— the South Sea Bubble, lotteries, mad and extravagant fashions and, most recently, Methodism (a new popular religious movement with a focus on social gospel preaching). By 1750, old social attitudes were also moderated by the rise of the new middle class (representing one third of the population).

The success of a propaganda campaign using a pair of satirical pictures by William Hogarth—Gin Lane and Beer Street—which depicted the misery gin drinkers suffered and contrasted them with the good health enjoyed by people who stuck to beer, paved the way for the new law. New social attitudes, and changing values within the population along with the interests of the brewers all likely contributed to the success of the campaign.